cell phone

-

Prosecutors to Congress: Let state prisons block cell phones

Top prosecutors across the country are again calling on Congress to pass legislation that would allow state prisons to interfere with cellphone signals smuggled to inmates. According to lawyers, the devices allow people to plan violence and commit crimes.

“We simply need Congress to pass legislation giving states the authority to implement cell phone jamming systems to protect prisoners, guards and the public at large,” 22 prosecutors wrote in a statement. Wednesday's letter to House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer.

Wilson's office said it plans to contact Democratic prosecutors and does not believe the matter is partisan.

The letter, obtained by The Associated Press, cites several crimes that lawyers say were orchestrated by inmates using contraband cellphones, including a drug conspiracy in Tennessee and a double murder ordered by an inmate in Indiana.

They also led a gang siege at a South Carolina prison in 2018 that lasted more than seven hours and left seven inmates dead. One prisoner described the bodies as "literally stacked on top of each other, like a horrible pile of wood." Corrections officials blamed illegal cellphones for the unfolding violence, the worst prison riot in the United States in 25 years.

“By preventing prisoners from using prohibited cell phones, we can prevent serious drug trafficking, deadly riots and other crimes,” prosecutors wrote.

To render the phones - which are smuggled into hollow footballs, implanted by corrupt employees and sometimes dropped by drones - worthless, prosecutors are asking for changes to a nearly century-old law A historic federal communications law that currently prohibits state prisons from using signal jamming technology to suppress illegal cellphone signals.

Efforts to crack down on illicit cellphones in state prisons have been going on for years, and South Carolina Corrections Director Bryan Stirling is leading an effort by correctional directors across the country to demand more technology to combat their use of smuggled phones. the behavior of.

In a progressive victory in 2021, the FCC passed a decision allowing state prison systems to work with cellphone providers to sequentially apply for permission to identify and shut down illegal cellphone signals. South Carolina was the first state to request use of the technology, but Sterling told The Associated Press on Tuesday that the state has not yet taken any action on the request.

Sterling said federal prisons can jam cellphone signals behind bars, but that is not currently the case.

CTIA, the wireless industry trade association, opposes interference, saying it could impede legitimate calls. However, CTIA told the commission that it has "successfully worked with its member companies" to "cease service for prohibited devices pursuant to court orders received," according to a 2020 FCC filing.

CTIA and FCC officials did not immediately respond to emails seeking comment on the new wave of subversion.

Congress has previously considered blocking the legislation, but has yet to sign any bill or even hold hearings. U.S. Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., reintroduced the measure in the last Congress in August.

"We're not going to stop advocating for this," Wilson told The Associated Press on Tuesday. "I can only hope that at some point Congress will take notice."

PR -

Representative Kustov Senator Cotton introduces the Mobile Phone Interference Reform Act

Congressman David Kustoff (R-TN) and Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR) have introduced the Cellphone Jamming Reform Act, a bill aimed at addressing the issue of contraband cellphone use in federal and state prison facilities. The purpose of this legislation is to allow prisons to utilize cellphone jamming systems in order to protect inmates, guards, and the wider public from potential harm.

According to Congressman Kustoff, putting an end to the illicit use of contraband cellphones within correctional facilities will have an immediate impact on reducing crime rates, enhancing public safety, and relieving the burden on our overwhelmed correctional systems. He stresses that this act represents a crucial initial step towards tackling the current crime crisis faced by America. Congressman Kustoff expresses his pride in collaborating with Senator Cotton to introduce such pivotal legislation and urges fellow members of Congress to offer their support.

Senator Cotton highlights how prisoners have been exploiting contraband cellphones for engaging in illegal activities outside prison walls, including orchestrating attacks on rivals, promoting sex trafficking operations, facilitating drug trade, and conducting business transactions. The use of cellphone gps jamming devices can effectively halt these criminal endeavors; however, current regulations under the Federal Communications Act prevent correctional facilities from employing this technology. This bill seeks to rectify this issue so that criminals serve their sentences without posing any risk whatsoever to society at large.

The Cellphone Jamming Reform Act has received endorsements from multiple state attorneys general, including Tennessee Attorney General Jonathan Skrmetti, Arkansas Attorney General Tim Griffin, South Carolina Attorney General Alan Wilson, Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond, Virginia Attorney General Jason Miyares, Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita, Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost, Alaska Attorney General Treg Taylor. The Act is also supported by the Major County Sheriffs of America, National Sheriffs' Association and the Council of Prison Locals.

According to Tennessee Attorney General Jonathan Skrmetti

"The only way to stop the illegal use of cell phones in prisons is through jamming signal. When individuals are incarcerated, they should not be allowed to maintain contact with criminal organizations on the outside. I commend Congressman Kustoff for his unwavering commitment to protecting our nation from organized crime."

Arkansas Attorney General Tim Griffin stated

"Congress needs to pass the Cell Phone Jamming Reform Act without delay. Prisoners are using contraband phones to carry out criminal activities from behind bars. We have the technology to enhance security and put an end to this illicit behavior; it's time we utilize it. I haven't heard any valid reasons why we should facilitate criminals and enable convicted felons to continue their criminal enterprises while in custody."

Background:

- The use of contraband cellphones is a pervasive issue within both federal and state prison facilities. Inmates exploit these devices to engage in a wide range of illicit activities, such as orchestrating hits on individuals outside the confines of the prison walls, operating illegal drug enterprises, facilitating unlawful business transactions, promoting sex trafficking, and coordinating escape attempts that put correctional staff, fellow inmates, and the public at risk. Incidents involving contraband cellphones have been reported nationwide.

- Over the past five years in South Carolina alone, there have been four significant cases of drug trafficking where operations were conducted clandestinely within prison walls using contraband cellphones. Notably, the most recent operation was directly linked to a Mexican drug cartel. Furthermore, in 2018, inmates affiliated with gangs orchestrated a merciless assault resulting in the deaths of seven inmates and numerous injuries through their unauthorized use of cellphones in a maximum-security facility.

- In Oklahoma, 69 defendants were found guilty of participating in a "drug trafficking operation that was primarily directed and controlled by incarcerated gang members using unauthorized cellphones from their state prison cells."

- In Tennessee, an inmate utilized an illegal cellphone to orchestrate drug conspiracy deals by sending a package filled with methamphetamine to his significant other.

- In Georgia, prisoners employed illicit cellphones to carry out fraudulent calls, demanding payment and even sending photos of injured inmates to their relatives while requesting money.

- As indicated by the Indiana Department of Corrections, during the previous year (2022), a gang enforcer incarcerated within Indiana Department of Corrections ordered a double homicide through the use of an unauthorized cellphone within prison walls.

- According to The Wall Street Journal's report, Martin Shkreli, the disgraced pharmaceutical executive who was sentenced to seven years for securities fraud, continued making decisions at Phoenixus AG with the assistance of an illegal cellphone.

-

Device illegally forcing phone muting

F.C.C. spokesman Clyde Enslin declined to comment on the issue or the Maryland case.

Wireless carriers pay tens of billions of dollars to lease spectrum from governments as long as others don't interfere with their signals. And there are additional fees. Verizon Wireless, for example, spends $6.5 billion a year building and maintaining its network.

"It is counterintuitive that this type of device has found a market at a time when wireless consumers' demand for improved cell phone coverage is clear and strong," said Jeffrey Nelson, a Verizon spokesman. These carriers also raise public safety concerns: criminals could use gsm blocker to prevent people from communicating in an emergency.

The CTIA, a major cellphone industry association, asked the F.C.C. on Friday to maintain the illegality of the interference and continue to pursue violators. The company said the move was in response to requests from the two companies to allow jammers to be used in certain situations, such as prisons.

The individuals who used the jammers expressed guilt about their vandalism, but some clearly had a mischievous side, and others gloated over the phones. "It was worth it just to watch those stupid teens in the mall get their phone hung up." Can you hear me? Noooo! Nice, "the jammer's buyer wrote last month in a review on a website called DealExtreme.

Gary, a therapist in Ohio, also declined to give his last name, citing the illegal use of the devices. Interruptions are necessary to get the job done effectively, he says. He runs group therapy sessions for people with eating disorders. During one meeting, a woman's confession was rudely interrupted.

"She was talking about sexual abuse," Gary said. "Someone's phone was turned off and they kept talking."

"There's no etiquette," he said. "It's an epidemic."

Gary said that despite the no-phone policy, calls always interrupt therapy. Four months ago, he bought a jammer for $200 and secretly placed it on the side of the room. He tells patients that if they are waiting for an emergency call, they should give the phone number of the front desk. He didn't tell them about the jammer.

Gary bought the jammer from a website in London called PhoneJammer.com. Victor McCormack, the site's operator, said he ships about 400 jammers a month to the United States, up from 300 a year ago. He says more than 2,000 holiday gifts have been ordered.

Kumaar Thakkar, who lives in Mumbai, India, and sells jammers online, said he exports 20 jammers a month to the United States, twice as many as a year ago. Clients include cafe and hair salon owners and Dan, a New York school bus driver, he said.

"The kids thought they were secretly hiding in their seats and using their phones," Dan wrote in an email to Mr. Tarka, thanking him for selling jammers. "Now kids don't understand why their phones don't work, but can't ask either because they'll get in trouble!" It's fun to watch them try to get the signal."

Andrew, an architect in the San Francisco area, said using jammers started out as fun and became a practical way to keep quiet on the train. Now he uses it more wisely.

"At this point, just knowing that I have the power to cut someone off is satisfying enough," he said.

One afternoon in early September, an architect boarded a local train and became a mobile vigilante. He sat next to a woman in her 20s who he said was "chatting" on her phone.

"She kept using the word 'like.' She sounded like a valley girl," said architect Andrew, who declined to give his last name because what he did next was illegal.

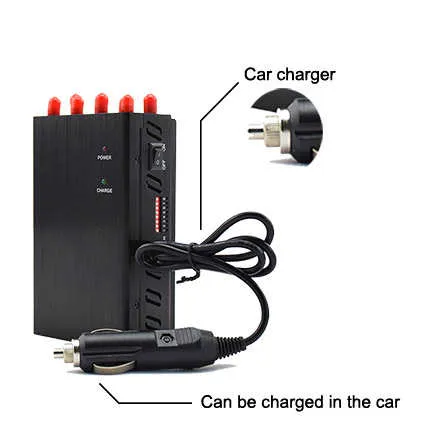

Andrew reached into his shirt pocket and pressed a button on a black device the size of a cigarette pack. It emits a powerful radio signal that interferes with the chatterer's cellphone transmissions as well as those of others within a 30-foot radius.

"She spoke into the phone for about 30 seconds before she realized no one was listening on the other end of the phone," he said. What was his reaction when he first discovered he could wield such power? "Oh my gosh! Liberation."

As cellphone use soars, making it difficult not to hear half of a conversation in many public spaces, a small but growing group of rebels are turning to a blunt countermeasure: cellphone jammers, devices that interfere with nearby mobile devices invalid.

The technology is not new, but foreign exporters of jammers say demand is increasing and they are sending hundreds of jammers to the United States each month, prompting scrutiny from federal regulators and the wireless industry last week. new worries. Buyers include cafe and hair salon owners, hoteliers, speakers, theater operators, bus drivers and, increasingly, public transport commuters.

The development is sparking a battle for control of the airspace over the ears. This damage is collateral damage. Insensitive talkers inflict mischief on the defenseless, while jammer device punish not only the perpetrators but also the more cautious chatterboxes.

"If there's one thing that defines the 21st century, it's our inability to back down for the benefit of others," said James Katz, director of the Mobile Communications Research Center at Rutgers University. "The caller thought he was rights outweigh those of those around them, and the disruptor believes his rights are more important.”

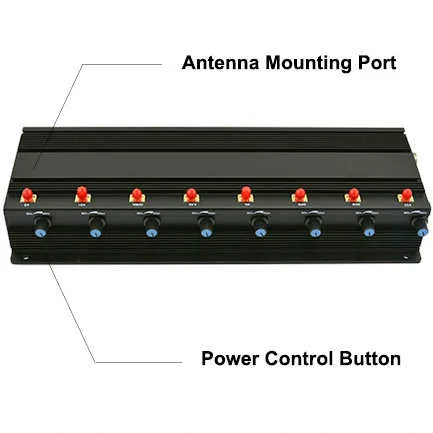

Jamming technology emits radio signals so strong that they overload cell phones and prevent them from communicating with cell towers. Ranges range from a few feet to several meters, and equipment costs between $50 and a few hundred dollars. Larger models can be reserved to create no-call zones.

It is illegal to use gps blocker in the United States. Radio frequencies used by mobile phone providers are protected in the same way as those used by television and radio stations.

The Federal Communications Commission says first-time users of cell phone jammers could be fined up to $11,000. His law enforcement agencies have prosecuted several U.S. companies for distributing the devices and are also prosecuting their users.

F.C.C. investigators said Verizon Wireless visited an upscale restaurant in Maryland last year. The store owner, who asked not to be named, said he spent $1,000 on a high-powered jammer because he was tired of employees focusing on their phones instead of customers.

"I tell them, put your phone away, put your phone away, put your phone away," he said. They ignored him.

The store owner said F.C.C. investigators spent a week there, using special equipment designed to detect jammers. But the owner has turned it off.

Verizon investigators were also unsuccessful. "He went to everyone in town and gave them his phone number and said if they had any questions to call him immediately," the store owner said. He said he had stopped using the wifi blocker.

Of course, detecting the use of smaller, battery-powered jammers, such as those used by disgruntled commuters, would be more difficult.

-

Greenville veteran suicide crisis prompts South Carolina officials to devise novel solutions to mitigate prisoner access to cellphones

This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Subscribe to the newsletter or follow The Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.

Shortly before noon on Sept. 11, 2018, a former Army soldier named Jared Johns lay in bed, turned on his iPhone camera, and said goodbye to his family.

Near the end of the two-minute video, Johns' eyes widened as a text message read on the screen: "She's calling the police and you're going to jail," it read.

Johns, who had served in Afghanistan, took a deep breath, placed a 9mm pistol under his chin, and pulled the trigger.

The 24-year-old veteran is one of hundreds of former and current service members who have fallen victim to a "sextortion" conspiracy. The scheme that led to his suicide involved scammers posing as underage girls on dating sites. Prosecutors said they sought to extort men who responded to their solicitations.

But the most startling aspect of the plot in Johns’ case was that it was allegedly carried out by inmates at Lee Correctional Institution, a maximum security prison in South Carolina about 150 miles east of Greenville. And the inmates did it using smartphones — banned devices that should have been blocked by the prison’s $1.7 million “managed access system.”

Now prison officials and some federal agencies have proposed purchasing an even more complex and potentially more expensive technology to stop illicit cellular and Wi-Fi messaging from contraband phones in prison: a jammer that will block all calls within its range.

“Inmates are incarcerated physically, but they’re still free, digitally,” said Bryan P. Stirling, the director of the South Carolina Department of Corrections, who has been on a mission to get signal jammers in prisons since 2009.

But some experts warn that jamming technology, which the federal Bureau of Prisons recently tested in a South Carolina prison, could put the public at risk by interfering with 911 calls and other cellphone service nearby. For rural prisons, the concern focuses on drivers on local roads and highways. Plus, they say, the technology probably won’t work.

“They’re taking an internal problem and impacting people who are not involved,” said Richard Mirgon, a former executive at the Association for Public-Safety Communications Officials. “It’s tantamount to saying, ‘Why not jam up the freeway to keep people from speeding in the side streets?’ It’s just so extreme.”

Problems with the best solution

The best solution, according to telecommunications companies and advocates for prisoners’ rights, would be to stop the influx of cellphones into prisons. But that has proven difficult,

especially at a prison like Lee, which has a long history of serious phone-related incidents. Inmates there have used contraband cellphones, for example, to order a hit on a corrections officer who was shot almost to death in 2010 and to publicize prison riots twice in the past four years.

Sex, drugs and cellphones:Relationships between guards, inmates unravel SC prisons

Prison officials at Lee say they have tried to stem the tide. In 2017, the corrections department felled large trees that loomed over the prison to stop drones from dropping off packages of cellphones. That same year, the department spent $8.3 million to install 50-foot netting at the perimeter of its prisons, including Lee, in hopes of stopping couriers from throwing backpacks of cellphones over fences.

Corrections officials say these solutions reduced the number of cellphones in state prisons. In fiscal year 2017, prison guards confiscated 7,482 phones, batteries or chargers in the state’s facilities, which house more than 21,000 people. In the fiscal year that ended in June, officials collected 3,900. Chrysti Shain, a spokeswoman for the corrections department, said that inmates now must spend thousands of dollars to acquire a phone.

Yet, the department acknowledges phones still get inside. Experts point to low-paid guards and prison workers who can augment their low pay by selling inmates contraband.

But even if cellphones get in, there should be no calls getting out. That’s because of the nearly $2 million in technology that Lee officials purchased to block calls from unauthorized phones.

Challenges with cellphone signal blocking

In 2017, after clearing the treeline and setting up the nets, the corrections department hired Tecore Networks, a communications company, to install the system that is supposed to detect and block all calls made from contraband phones. The technology is supposed to work like this: If someone makes a call, the system compares the cell number to a predetermined list of prison staff phone numbers — called a white list —and then either allows the call to go through, or blocks it.

The wireless telecommunications lobby group CTIA, which represents some of the country’s largest carriers and equipment manufacturers, has recommended that prisons use the managed access systems, as they are called. But it’s unclear how many facilities across the country actually do. Shawntech, another private company that sells managed access systems to correctional institutions, says it provides the multi-million dollar systems to close to 350 jails and prisons.

Even engineers who back the system as a solution warn that it’s not a silver bullet to stop all illicit calls, which can circumvent the system because of a very basic rule of how a cell tower works: If you can’t see it, it can’t see you.

When someone inside makes a phone call, the closest cell tower will pick up that signal. In a prison with a managed access system in place, the tower is usually located within the perimeter. But, for example, if an inmate stood behind a wall with water pipes, the cell signal would find the closest tower it could see, which would be outside the prison.

Also, cell companies often change the strength of a signal if customers in an area have bad reception. It’s like listening to two conversations happening at once in the same room; it’s easier for you to hear the loudest speaker. Whenever cell companies boost a signal, cellphones inside the prison will be able to find it more readily. It’s a problem that Tecore flagged in a 2018 press release.

That’s what South Carolina’s corrections officials say happened at Lee, and how the inmates contacted Johns in the first place.

Current and former prisoners at Lee said they could use cellphones easily, even with the managed access system in place. This year, inmates at Lee were caught live-streaming on Facebook.

“Walk into one room, and it’s fine; walk into another and you won’t be able to,” said a current inmate in the prison, who said he has used a prepaid Boost Mobile cellphone to make calls. His identity is not being revealed out of concern for his safety.

Tecore, which manages the prison’s system, did not respond to multiple emails or calls over several weeks seeking comment.

Jamming all calls, even to 911

These problems explain why corrections officials and federal agencies have proposed using technology long opposed by the communications industry: cellphone jammers to stop all calls, even from phones owned by staff or emergency workers.

Unlike managed access systems, which allow people to make calls if their numbers are on an approved list, a jammer is indiscriminate in its reach and power to block all frequencies, including data and Wi-Fi. That’s a problem for the nation’s 911 phone system, which operates on a frequency close to the one commercial carriers use.

Only federal authorities can legally use jammers, and only in limited circumstances involving national security. But with the blessing of the FCC’s Chairman Ajit Pai—appointed by President Trump in 2017— and the U.S. Department of Justice, prison jammers could become a possibility.

In September, the department and state officials put out news releases saying that a test at South Carolina’s Broad River Correctional Institution showed that a micro-jammer could block calls inside a cell block while allowing “legitimate calls” a foot outside its walls.

But a technical report on the same test by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration was squishier. It noted that the test involved only one of the 14 gsm jammer required to block calls in half the cellblock. And it found that jamming was detected at least 65 feet away, though it said it was unclear how significant that interference would be to regular cell-phone service.

The telecommunications agency would not comment on the study.

Precise jamming — limited to a specific distance and also only to cellphone frequencies— is prohibitively expensive, especially for larger correctional facilities, said Ben Levitan, a technical engineer who has worked with the South Carolina corrections department in the past and read the NTIA’s report.

That kind of jamming is “cool in theory, but it’s impractical,” he said.

A 2018 T-Mobile report also concluded that jammers with the precision to overpower only phone frequencies up to a certain distance would generally be too expensive for prisons.

-

FCC Cracks Down on Mobile Phone Jammers

The Federal Communications Commission says illegal devices that block cell phone signals could pose a security risk.

The FCC has seen an increase in the sale of jammers devices that block cell phone calls, text messages, Wi-Fi networks and jammer GPS systems and could be used to wreak havoc in public places.

The small, battery-operated devices can be used to create "dead zones" in a small area (usually about 30 feet) and are used by movie theaters, restaurants and schools to keep people away from their phones. But they also disrupt emergency calls, can disrupt navigation near airports, and have been used near police stations to disrupt radio communications. FCC officials said they have noticed an increase in jammers banned under federal law entering the country. Many cheaper versions are imported from Asia and sell for as little as $95, according to the agency.

The sale, advertising, use or import of jammers is illegal under the Communications Act 1934, which prohibits the blocking of radio communications in public places.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) cited eight individuals and companies for ad-jammer ads on Craigslist.

According to the FCC, the jammers were advertised on websites in Orlando, Philadelphia, Austin, Mississippi, Charlotte, North Carolina, Washington, D.C., Cincinnati and Corpus Christi, Texas. Officials said they do not believe the cases are related.

"Merely advertising signal jammers on sites like Craigslist.org violates federal law. Signal jammers are contraband for a reason," FCC Enforcement Director Michele Ellison said in a statement expressed in. “One person’s moment of peace or privacy may well endanger the safety and well-being of others.”

According to the citations, most sellers advertised the jammers for "an undisturbed nap" on the bus, keeping classrooms quiet, or keeping the area "free of nuisances," but there was no suggestion that the device might be used for more nefarious purposes .

"We are increasingly concerned that individual consumers who use jammers appear to be unaware of the potentially serious consequences of using jammers," one of them was quoted as saying. "Instead, these operators mistakenly believe that their illegal activities are for personal convenience or should otherwise be excused.”

But the FCC said at least one seller appeared to know the jammers were contraband.

Keith Grabowski reportedly advertised a "cell phone jammer, Wi-Fi jammer" on Craigslist in Philadelphia for $299.99. He said in the ad, "with few details given due to the nature of the item," that the jammer "is not a toy" and "I just want to get rid of it as quickly as possible."

"The nature of his complaint indicates that Mr. Grabowski was aware of the sensitive and/or illegal nature of the equipment he was selling on Craigslist," his citation reads.

Those facing charges have 15 days to remove the ads from the site and provide the FCC with information about where the jammers were purchased and to whom they were sold. Merely advertising a jammer for sale could result in fines exceeding $98,000.

The FCC has established a jammer reporting hotline to notify the agency of people who may be selling or using jammers.

"We intend to take more aggressive enforcement action against violators," Ellison said. "If we find you selling or operating a jammer, you will pay a high price."